Dartmoor's Pygmy Forest' is taken from Forest: Walking Among Trees, a new book by writer Matt Collins and photographer Roo Lewis, exploring the link between trees and their wooded heritage.

The undulating path leading to Wistman's Wood is flanked by the charred remains of gorse brush. Their twisted stems, cut short and blackened, are a clear indication of a managed landscape. These are the remnants of a recent swale', a process whereby overgrown and dead material (primarily gorse) is systematically burned, provoking the regeneration of grassland. Swaling on Dartmoor National Park in South Devon has been practised for centuries, carried out by its respective landowners under controlled conditions. While the annual clearing prevents wildfires and improves habitat for ground-nesting skylarks, it also maintains an open, grazeable grassland for livestock; an exercise therefore of compound motive. Burned gorse, if you like, sets the tone for Dartmoor as a whole: a wild and dramatic terrain, offset by its agricultural heritage.

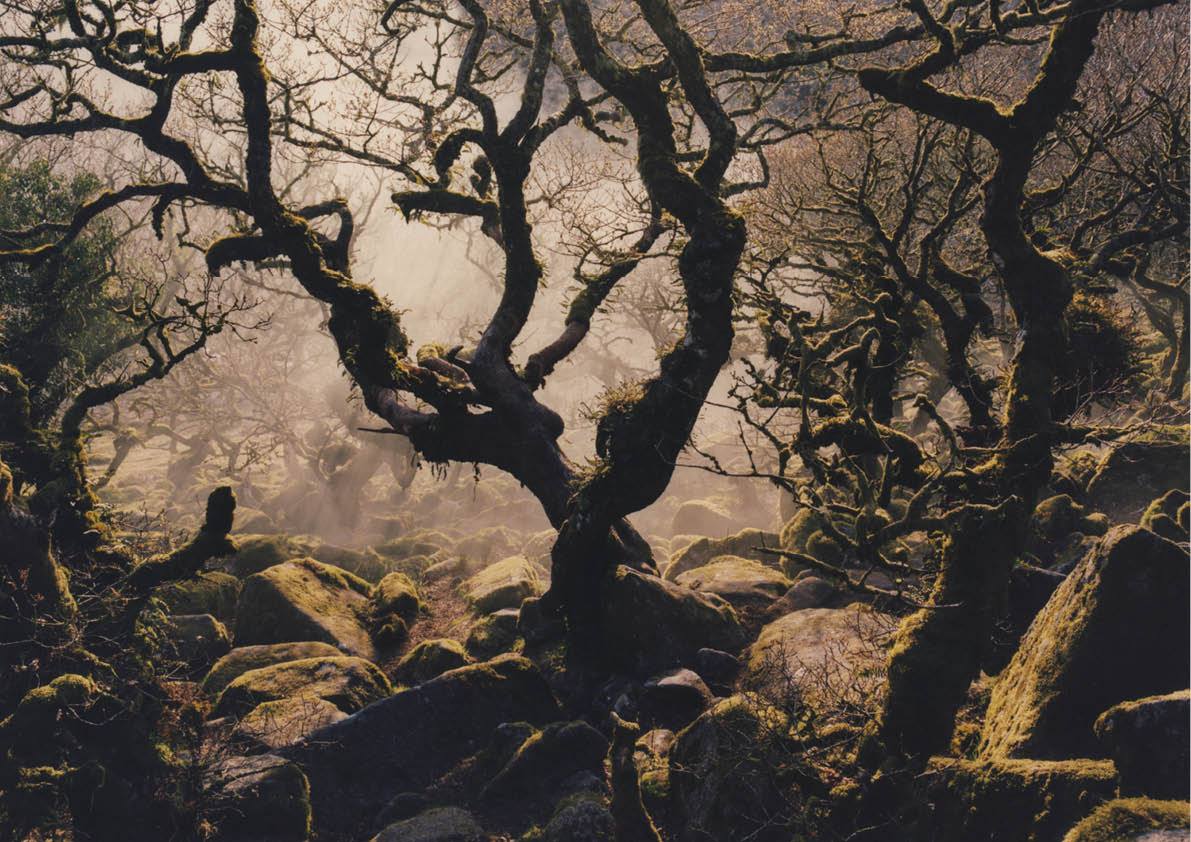

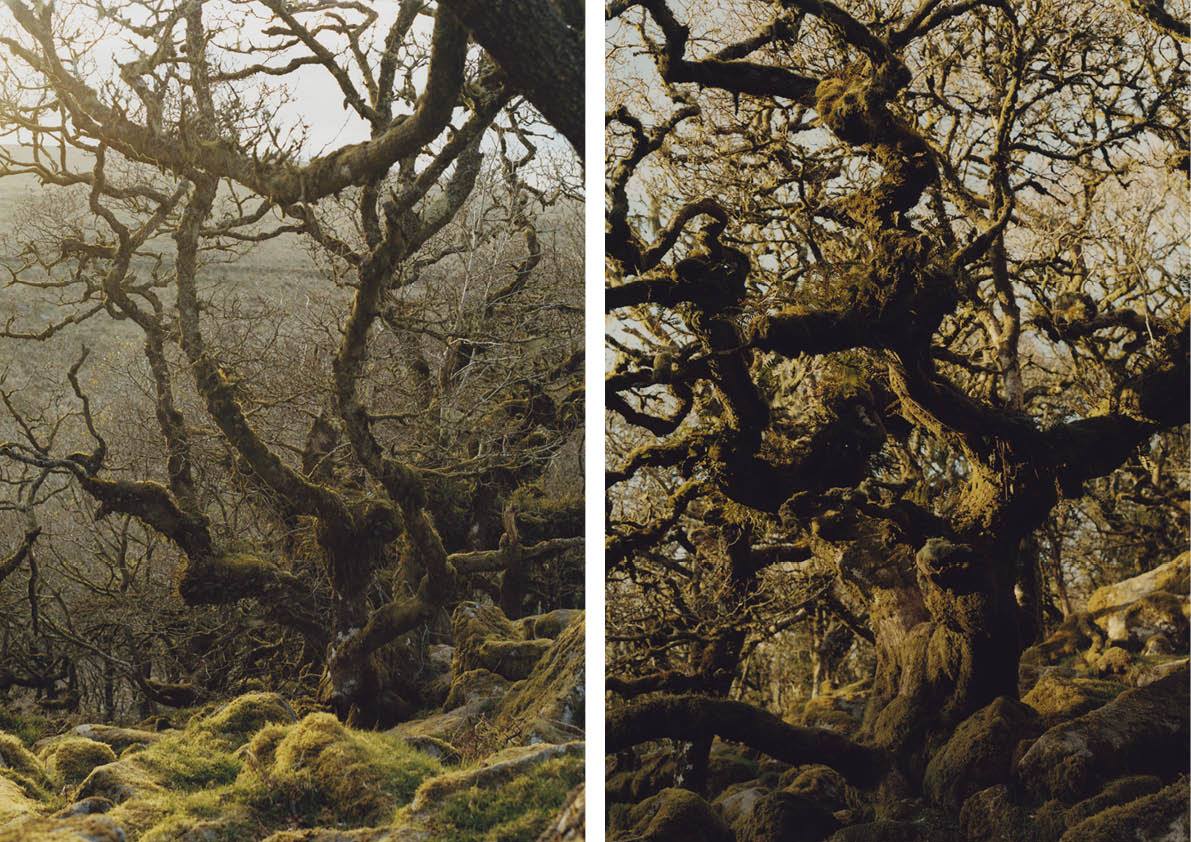

It is one of the wilder spots within Devon's vast and rocky moorland that I've come to see: an isolated wood at the very centre of Dartmoor. Wistman's (or Wise Man's') Wood is 9 acres of strikingly gnarled and stunted pedunculate oak trees, known best for its resemblance to a truly enchanted woodland. As a rare example of native upland oakwood, this small and ungainly grove of trees is one of Dartmoor's hidden gems, set above the West Dart River and shielded in the gully between two unassuming hills. The wood's solitary position within its barren surroundings is the first of three factors leading to its bestowed notoriety. The second is the eerie, low-lying and moss-clad nature of the oaks themselves, and the third its association with pagan tradition and druid folklore. Almost all accounts of Wistman's Wood come laden with conjectural haunting. There are tales of ghostly processions passing through the trees at night, and it is said to be the home of the Devil's hounds', mystical black dogs who roam the wood, thirsty for human blood. For me, the combination of horticultural niche and paranormal pomp formed too irresistible a lure.

The walk from road to wood stretches just over a mile, the thicket ahead looming compact and dense. Not yet spring, leaves are only opening on the earliest of deciduous trees; the distant oaks are still some weeks from breaking their winter dormancy. The absence of fresh leaf gives their branches a russet, wintry tone, and the trees form a discernible clump; together a tangible, contained little forest.

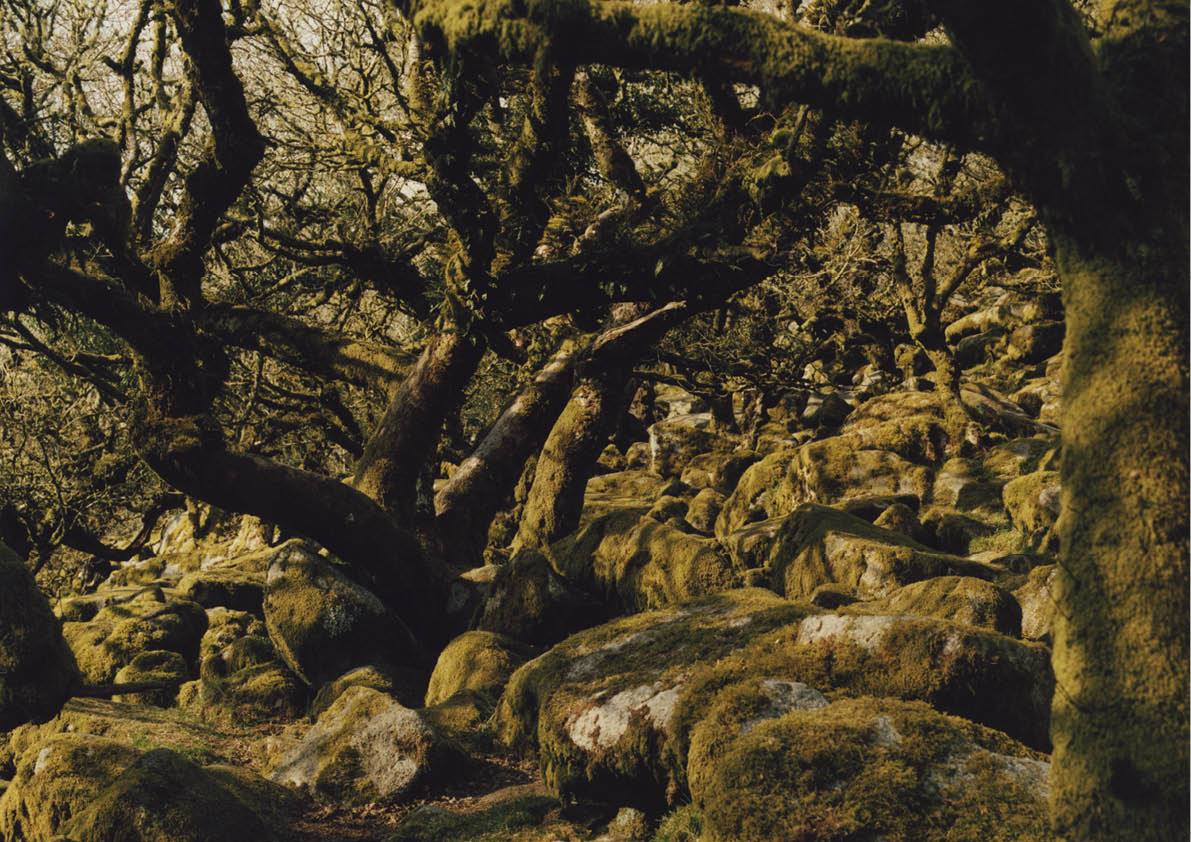

At the entrance to the wood I'm met by a small group of Dartmoor ponies. They are affable, tough little things, and their presence on the moors has been documented for hundreds of years, first as workers, now as free-range grazers. They shift a little as I pass, and one particular individual, a tubby bay, confidently approaches, hopeful for a snack. But at the threshold of the wood is where the ponies remain, as they are prohibited entry by another of Dartmoor's intrinsic components, a carpet of uneven granite boulders. Nearly all of Dartmoor sits on granite, and it is thought that the historic mining of this rock is one of the reasons for the ponies being brought onto the land. Wistman's Wood itself thrusts from a clutter of exposed boulders, its oak roots weaving down beneath and through the crevices between them. The stones therefore, uneven and difficult to negotiate, form a protective defence against grazing mammals, allowing the trees to flourish within, inaccessible to hungry livestock.

To enter a wood is to pass into a different world,' wrote the late nature writer Roger Deakin, a sentiment never truer than of Wistman's. The combination of eerie oak and cumulus boulder is a striking visual contrast to the world outside it. A chaffinch, present and loud on a bough of a circumferential tree, stays with the ponies as I make my way in. Inside, the wood is quiet. As the granite obstructs animals' passage, so do the oaks temper the wind; a few feet in and already the air is still. There is in fact no movement in the trees at all. Moss hangs undisturbed from twisted branches, interjected at points by motionless fronds of epiphytic ferns.

From below the wood the West Dart is faintly audible, emphasised by the silence in the trees. Without leaf break the canopy is more open than it appeared from the path, and intermittent gaps in the clouds above allow occasional bright illuminations. With these sporadic sunbursts the entire colouration of the wood is transformed: the dull green moss morphs into a striking yellow, while the oak trunks and branches lift to ochre-orange. The stones also light up and are thrown into relief, revealing distinct and irregular shapes. In such a light it becomes difficult to grasp any sense of a supposed sinister, underworldly atmosphere. I try to imagine, for the sake of due deference, what it might be like to visit this wood in less genial weather. Perhaps in winter, or perhaps at dusk, without sunshine to hamper the ghouls. All the same, Wistman's Wood continues to feel remarkably unspooky', albeit lacking in visible fauna.

Appearing between stones I spot the dainty white flowers of wood sorrel (Oxalis acetosella), their angular leaves splayed close to the ground. There are numerous runs of bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus), particularly in the higher reaches of the wood. These dwarf shrubs are covered in red springtime flowers; little pods that will form rich edible berries later in the year. The oaks themselves support a great wealth of botanical life inside their branches. Sprouting from one individual are arches of bramble, flowering woodrush and the trunk of an advantageous rowan tree, not to mention a substantial clothing of mosses and colourful lichen. After the oaks, rowans make up the bulk of Wistman's trees. Those sympathetic towards the mythology of this wood might read the rowan's presence as further confirmation of its mystical nature. Not only does the tree possess its own folklore heritage, but those found growing from the crevices of larger species are also deemed by some to ward off the presence of witches. For the more sceptical, however, the rowans are a typical companion plant found in pedunculate oak woodlands, especially of this topography and altitude.

"Perhaps it is the oaks themselves, rather than any ghoulish entity within, that endow this forest with its unnerving, mysterious figures."

The origin of Wistman's Wood is, as one might expect, not entirely clear. A study carried out by English Nature suggests that the oak grove may be a surviving enclave of a much larger natural oakwood, possibly dating as far back as 7000BC. It is likely that this parcel of forest was consciously spared as surrounding trees fell to grazing land. But typical of most pygmy' forests, the arboricultural dwarfism is more directly the result of environmental factors, such as poor soil and high altitude. Wistman's Wood grows on land owned by the Duchy of Cornwall, which encompasses some of the highest of Dartmoor's tors. Residing at around 1,300ft above sea level, it is one of Britain's most elevated oak forests, and the stunted tree habit makes it a true rarity of its kind. In 1964 the forest was selected as a Site of Special Scientific Interest, now protected by law and conserved by Natural England.

Before I leave to retrace my path back to the road, I sit for a moment on a larger protruding boulder positioned towards the outer edge of the wood. The trees gradually thin out near the lower reaches, with a few individuals standing alone just outside. Their form appears even more unique and misshapen when viewed in this way, isolated and removed from the group. The sun is going down and, as I get up to leave, it passes unexpectedly through a gap in the clouds. The sudden burst illuminates the entire wood and the rock I'm sat on lights up beneath me. The granite sparkles, as it does throughout the forest, shining like glitter from a surface of scattered stones. With the sun on its final glow before setting behind the hill in front, it's noticeable for the first time that in fact Wistman's oaks appear to be facing it, leaning in towards it. Growing out from the hillside gradient they are a congregation of sorts, like worshippers in an auditorium, with arms reaching forward. I stand with the trees, drawn into the fading light, as if enacting some quiet springtime ritual. Perhaps it is the oaks themselves, rather than any ghoulish entity within, that endow this forest with its unnerving, mysterious figures.

Words by Matt Collins. Images by Roo Lewis.

Add a comment